As student enthusiasm grew with each Rites of Spring, so did administrative apprehension. Among those watching as the event mushroomed was a Student Affairs leadership team of then Vice President Neal Gamsky; his Associate Director, Jude Boyer, M.A. ’68; and Mike Schermer ’73, M.S. ’78, who was director of Student Life and Programs.

The trio worked directly with students. Schermer had attended the event as an undergraduate. Together they understood as well as any staff the level of passion students maintained for Rites, which Schermer noted became as much a part of ISU’s culture as Avanti’s and Pub II.

But they also realized disaster was looming on the horizon.

Security concerns that surfaced at the second Rites grew exponentially each year with the number of people on the Quad. And there was no way to prevent outsiders from attending—including community teens.

“The inability to restrict the event to Illinois State students became the real issue. You blend in high school kids and other college kids and you lose any control,” Boyer said.

Maintaining order was a concern Mis voiced at the second Rites. With more than double the attendance from the previous year, trouble arose. There were six injuries, according to Vidette reports, and one serious drug overdose requiring a hospital visit.

More was done the third year to restrain participants. The date was again kept secret, and yet approximately 10,000 attended. Vidette reporters wrote that 19 people were treated for minor injuries, including cuts from glass. Tires were slashed in a nearby parking lot, and a Co-op Bookstore window was broken.

“That year it moved to the center of the Quad. It still wasn’t that bad, but there were enough problems to create cause for reflection,” said Gamsky, who watched each year from his office window on the top floor of DeGarmo Hall as the events unfolded.

From that vantage point there was no missing the haze that hung over the Quad as a result of so many joints being passed through the crowd. The illegal activity was contained to the campus, where officers from the Town of Normal did not venture.

“The Normal police, whether they liked it or not, could not come on campus. They had no authority, so they stopped at the edge,” Boyer said. “The students were high and drunk but not dumb. They stayed on the Quad.” And while there were ISU police monitoring the event each year, they took a subdued stance.

The issue of drug use and the tensions it created overall within the community and across campus began to be addressed during that year of 1974. A Multi-County Enforcement Group formed, conducting residence hall drug raids in December. By January of 1975 the University had created a committee on drug concerns, which recommended an Alternate Rites of Spring be held in Hancock Stadium so that admission could be limited and the crowd contained to bleachers.

“The decision was an unpopular one to those students who thought of Rites of Spring as the most valuable experience of the school year,” History Professor Emeritus Roger Champagne documented in his Illinois State book titled A Place of Education.

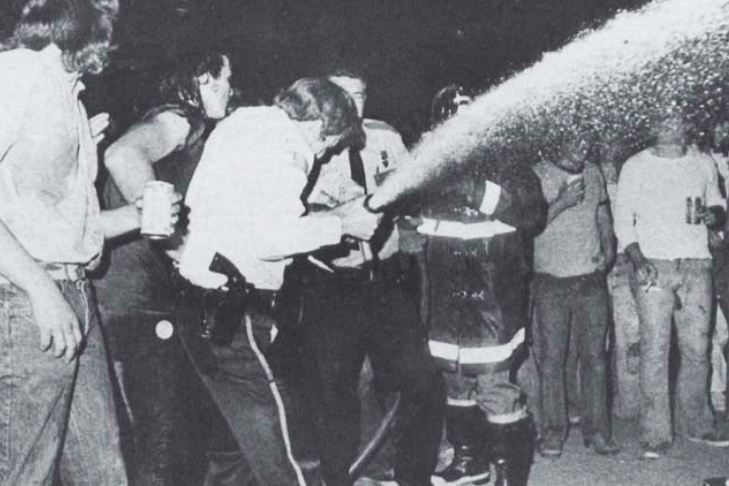

The lack of interest was reflected in attendance, which plummeted to 4,000. Students determined to stage a traditional event gathered on the Quad, with those leaving Hancock joining in for an “alternative Rites.” A bonfire was started and fire officials called to extinguish it. The Vidette reported beer cans and rocks were thrown at the firemen as the group dispersed. One student charged by the University as an organizer of the melee left the University.

Despite the drama, Rites returned to the Quad in 1976. This time students needed to obtain a button for admittance. The crowd reached 12,000, in part because of a Vidette blitz.

“The Vidette was asked to be cooperative and help us keep it an ISU event, but they sent flyers to other university newspapers,” Gamsky said. “We had people come from Missouri, Michigan, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Texas.”

The problem was recognized among student leaders. “Over the years the word started to spread that we were having this fabulous party and people should come. We started getting more and more people who didn’t care about ISU at all,” Catanzaro said.

The influx of outsiders reached a critical level at the 1977 event, which became so enormous and unruly it led to the demise of Rites of Spring. Buttons were again distributed, and yet more than 18,000 people made their way to the Quad. Some estimates place the number closer to 25,000.

“Rites was free for anybody who came, and that last year I would guess that close to half in the crowd were not ISU students,” Catanzaro said. “We were putting on this event for people who had no ties to ISU, no commitment to the University, and no appreciation for the campus.”

Bus loads of students arrived from out of state. They were joined by motorcycle gangs from Chicago—some of whom offered to serve as security. High school students again joined some from the community until people were “jam-packed from Hovey Hall to the fine arts buildings and back to the bridge area by Milner,” Gamsky said. “They camped out on the Quad. They were cooking chicken. Everybody had pot.”

ISU police joined Gamsky, Schermer, and Boyer that year in the top DeGarmo Hall office, which became command central for 24 hours. Determined to get a sense of what was happening within the crowd, Gamsky ignored Schermer’s advice and headed into the crowd wearing a three-piece suit.

“I wanted to get a ground’s eye view,” Gamsky said. If what he saw as he cautiously stepped over bodies wasn’t enough to confirm reason for alarm, being pelted in the head with a cup of beer gave Gamsky plenty of evidence that Rites was beyond control.

“In my mind it was only a matter of time until someone was killed or maimed for life,” Gamsky said. “It is a borderline miracle nobody died or was seriously injured.”

Schermer came to the same conclusion. “It was an out of control crowd filled with people who were obviously taking illegal drugs and not handling them very well, I might add,” he said.

Catanzaro volunteered to work at the last Rites, and is haunted by the memory of what she witnessed near the side of the stage. “I was watching as the crowds pushed closer and closer, knowing that somebody could really get hurt in that crushing because there was no place to go,” she said.

While primarily a peaceful crowd, judgment was seriously lacking. Schermer recalled that during the last Rites people were hanging from light poles, with others trying to get on rooftops of buildings surrounding the Quad. One person drove a car down a sidewalk.

“Kids stoned out of their minds were falling out of windows and trees,” Gamsky said, recalling ambulances were on stand-by and cots were in place when the need arose to carry people out.

Reports from The Pantagraph and Vidette document more than 80 people were treated on the campus for injuries, with six going to the local hospital. The majority of those individuals were not Illinois State students. Three were there for a drug overdose.

Beyond the medical issues, there were arrests for open alcohol outside the Quad, arrests for possession of cannabis, and nearly 100 complaints to the Normal Police from individuals in the community disgruntled by the loud music.

But perhaps the most unexpected tragedy was a scarred campus.

“There was garbage up to your knees, literally. It was a sea of garbage,” Schermer said. Boyer recalled the odor was as repulsive as the ugly piles of trash. “It stunk to high heaven of urine and beer,” she said.

“Trampled chicken bones, Styrofoam from torn-up coolers, crushed apples, bottle tops, metal can tabs and other remnants of the day-long party were spread out amidst the matted grass,” The Pantagraph reported.

Gamsky’s memory of the morning after that 1977 event is even more vivid. “I looked out over the Quad and it was shimmering as the sun hit the broken glass and bottle tops. It looked like water,” he said. The condition was made more sad by the fact Rites of Spring that year had a theme of safety and ecology.

Catanzaro, then student representative to the Board of Regents, has a similar memory. “I looked out over the Quad from a Hovey Hall window that Monday morning following and actually had tears in my eyes because of the damage that had been done,” she said.

Illinois State students made a serious attempt to restore the Quad. Kimberly Theobald ’78, who was vice chair of security for Rites in 1977, submitted a written report to Gamsky describing the effort. “Ten, 20-yard dumpsters, which were overflowing, were removed from the Quad. A student group of around 150, which dwindled to 10 by 4 a.m., picked up that amount of garbage. A very small group worked the better part of Sunday to begin picking up the smaller pieces,” Theobald wrote.

So much trash remained embedded in the grass that the University’s Environmental Health and Safety Office declared the Quad unsafe and roped off the area.

Grounds employees worked overtime to restore the Quad. The $24,000 undertaking had just begun when Lloyd Watkins arrived on campus as a finalist to replace outgoing President Gene Budig.

“They carefully chaperoned me around the mess on the Quad. They made a great effort to shield me from how bad it was,” Watkins said. Having arrived from Texas, he was unaware of Rites of Spring. That changed on his first day in office.

Reports from Gamsky and the other vice presidents, as well as student body leaders, were waiting on Watkins’ desk. All recommended Rites never take place again. Watkins quickly came to the same conclusion.

“I found out how bad it was, and I was appalled. It was very clear that this had to come to an end,” Watkins said. “I studied the whole situation the first week I was president of Illinois State University, and then issued a statement that canceled Rites of Spring.”

Watkins gave six reasons for the decision that came July 25, 1977—just 10 days after he became the University’s 13th president. He gave Gamsky the directive to work toward “an acceptable, responsible, and controllable alternative Rites of Spring.” The result was the start of Springfest.

Knowing he was killing a beloved tradition, Watkins purposefully made the announcement during the summer session. There was some anger when students returned, and Watkins was booed at events such as Homecoming for a couple years. But he never regretted the decision, which he said was made easier by the full support of the top administrative team, faculty, and student leaders.

Several students joined Theobald in signing a letter to Gamsky that stated “the concept of Rites is excellent, but the concept is about the only thing which is positive about this event.” They recommended that “Rites of Spring at Illinois State University never take place again” because “the students have proven that they cannot handle it; therefore this privilege must be permanently revoked.”

Watkins appreciated the student leaders explaining to their peers why he had no choice but to end what had started as a bold innovation and become a cherished tradition.

To this day he is remembered by many an alum as the president who killed Rites of Spring. It’s a label he considers a compliment, as he remains convinced he made the best decision for Illinois State.

“For me the most important thing was that Rites of Spring did nothing to advance the educational goals of the University, nothing at all. In fact it was an event that was ruining the good name of Illinois State University,” Watkins said. “I was not going to let ISU become the party school.”

Why did Rites of Spring end?

Less than two weeks after becoming Illinois State University’s 13th president, Lloyd Watkins made the announcement that Rites of Spring was canceled. A news release issued in July of 1977 listed six reasons for the decision.

- Rites of Spring was not, and never could be, a controllable event.

- The potential for serious injuries or fatalities is high.

- The laws of the State of Illinois and the regulations of Illinois State University were repeatedly disregarded during past Rites of Spring.

- The costs of the event, direct and indirect, were very high.

- Damage to university grounds and buildings has been severe.

- The event offers no apparent contribution to the educational mission of the University.