On May 19, 1970, the Illinois State University campus reached a boiling point leading to what has become known as the “flagpole incident.”

Tensions escalated on that Tuesday afternoon on the Quad over a seemingly simple decision—when and for whom the flag on the Quad should be lowered to half-mast. A single politicized flagpole ensnared a growing student body activated by national and local political forces and racial inequality, and a neighboring community unsettled by change. University administrators were caught in the middle.

Appears InThe flagpole moment was the largest of many confrontations at ISU from 1968–1970. Nearly 50 years later, those who were on campus can still vividly recall that event and all those crazy days of May, followed weeks later by the end of Samuel Braden’s presidency.

“There’s nothing quite comparable to this in our history,” said Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus John Freed. “It’s such a confrontational moment.”

The University’s rapid expansion in the 1960s led to problems with the Town of Normal, where some residents and officials resented the campus’s encroachment. Tensions on and off campus were exacerbated when the University dramatically expanded its enrollment of African-American students through the High Potential Student (HPS) recruitment program, which brought hundreds of additional black students to a town that still discriminated against them, and to a campus where they were marginalized.

George Pruitt ’68, M.S. ’70

First Black Student Association president, former High Potential Student Program director

When I transferred to Illinois State in 1967, African-American students were severely underrepresented in the student body and in the faculty and in the administration, and we were concerned about it. There were probably about 150 black students in the whole university. So we began to protest.

Charles Morris

Professor of Mathematics emeritus (1966-1995), first Academic Senate chair (1970-1971), former Administrative Services vice president

The community was typical for the period. We had trouble finding housing. At that time, there were just three of us African-American faculty members.

George Pruitt

In spring 1968, the University committed itself to a major recruitment drive through the HPS Program. We basically used the students that we had on campus to go back to their home communities and home schools to recruit black students out of Chicago and the St. Louis area.

Charles Morris

We tripled the number of black students in the first year of our recruitment. There were various problems. The African-American students were not provided housing of the same kind that was available to Caucasian students. Some lived in homes in Bloomington, but none of the Normal renters, homeowners, accepted African-American students at that time. The African-American students had to cope with hostility and resistance.

Karen Williams ’72

Black Affairs Council student leader

Before move-in my roommate and I contacted each other through letters, to buy matching bedspreads and all that. I got there, to Atkin-Colby, first. I was waiting there anxiously, left the door open for her. The roommate and her family showed up. They looked inside and saw me, closed the door, and never came back. Eventually, I was given another roommate. She was asked if she minded having a black roommate. I was never asked if I wanted a white roommate.

George Pruitt

The HPS Program was not just about recruiting students and having students achieve. Our broader objective was to change the culture of that university, to make it broader, make it more inclusive.

John Freed

Distinguished Professor of History emeritus (1969-2012)

Another factor is this incredible expansion with the baby boomers. ISU went from 4,000 to 14,000 students in a decade. It’s this incredible transformation of a rather sleepy teachers college into something else.

Bob Lenz

ISU attorney (1967-1973), advisor to President Samuel Braden

In those days, by and large, some of the old-timers in Normal would’ve been very happy to have a giant chain-link fence put up around campus.

Dave Anderson

Town of Normal city manager (1965-1998). (Photo courtesy of The Pantagraph)

Some of the people in the University administration—they were good people, but they felt the University could do any damn thing it wanted to do, and to hell with the town. Some of us that worked for the town felt a certain amount of displeasure with that.

John Freed

Normal was a very conservative community suddenly confronted by the outside world.

Dave Anderson

There were two camps for Normal residents. One was saying it was a college campus, what the hell do you expect? The second camp just wanted us to go in and bust their heads. There wasn’t much in the middle.

Many Illinois State students and faculty joined the anti-Vietnam War and civil rights movements. They largely operated in parallel to each other on campus, with white students and faculty mostly participating in the former, and black students and faculty involved in the latter.

Bill Cummings ’71, M.S. ’78

Vidette photographer

The Vietnam War was going on. The civil rights movement was in full bloom. Martin Luther King had just been killed. Bobby Kennedy too. The country was up for grabs.

Rose (Osing) Yount ’72

Student body vice president

You saw this uprising of student groups in response to social issues that were blowing up left and right. Rumors were abound. It was a very, very frightening time.

Bill Cummings

Don’t forget there was a draft. A lot of us were sucked into that.

Charles Morris

Black students’ focus and concerns were strictly on black student issues. The Vietnam protesters were a separate group. These events were bubbling up at the same time, so it was hard to tell which was which or who was protesting what.

Karen Williams

I can remember one incident getting out of hand. We were all supposed to go to Milner Library and get one book and displace it. We wanted to disrupt but not destroy. They ended up locking down the library. It got out of hand. Those who wanted to stop the war were trying to get involved and help us, but the war effort would’ve drowned out what we were doing. We were fighting to keep it separate.

Janice Cox ’73

Student activist

There were a lot of groups actually at the time. They sometimes worked at cross-purposes, but sometimes worked together too, as people sorted out their philosophic positions and their political positions as they dealt with all the other issues that were coming up. You know, racism and sexism. All of that entered into the mix.

Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, two state leaders in the revolutionary Black Panthers organization, were killed during a police raid in Chicago on December 4, 1969. Their deaths galvanized black leaders at ISU, leading to the first—but not last—confrontation over the flagpole, as well as demands for change.

Karen Williams

ISU did a lot to respond to our needs. We did get a series of speakers the following year. Andrew Young, Jesse Jackson Sr., and Nina Simone came too.

George Pruitt

One of the speakers that we invited was Fred Hampton. We got to know Fred. One of Fred’s lieutenants and friends was a guy named Mark Clark. Mark Clark’s sister was a student at Illinois State. When Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed by police in Chicago during a raid on their apartment, it was a sad day for us at Illinois State and it was personal. These were not some distant figures. These were people that we knew and respected and liked.

Alonzo Pruitt

Student (1968-1971), Black Student Association leader

I was very angry. That’s what started it for me. I went and put the flag at half-mast.

George Pruitt

The governor’s office called President Samuel Braden and ordered him to raise the flag to full-mast and told him he didn’t have the authority to lower the flag, only the governor or the president did. We weren’t happy with it, but we also trusted President Braden and we knew it was coming from the governor and not him. We went back to the flagpole and disbanded. And someone raised the flag back up, and that was the end of it.

Virginia Owen ’62

Professor of Economics emerita (1962-1993), College of Arts and Sciences dean (1982-1993)

Everybody was up in arms. Somehow it kept growing and mushroomed, and one day President Braden walked into the old cafe that was in the Old Union, which had been taken over by black students. It was a very hostile crowd, but he walked in and said, “What’s the problem?” and started talking to them.

George Pruitt

There were just a lot of things happening simultaneously. We petitioned the student union building be named in honor of Malcolm X.

Charles Morris

I was on the Task Force on Inter-Group Relations, which made the recommendation to the University Council that a building be named after Malcolm X. Although I had the preference at the time for someone else, I felt for the goals that the student organization was trying to achieve certainly that Malcolm X suited their interests and many of them are closer to him in say lifestyle and attitude than I, but I was willing to support it.

George Pruitt

Malcolm X had more currency and following in the urban north than Martin Luther King did. We loved Dr. King. But in the urban north, Malcolm was much more effective in tapping into the anger.

Alonzo Pruitt

Asking for the renaming of the union for Malcolm X, I think that was one of our big mistakes. They were willing to name a building after Dr. King. But some of the people in our group insisted it was Malcolm X. It was a mistake, because we wound up getting neither.

George Pruitt

President Braden was told in no uncertain terms by his Board of Regents and by others that an action on his part to do that would have long-lasting and significant damage to the University in terms of funding and political support. Braden took that recommendation to the board but chose to personally disagree with that.

John Freed

We never renamed that building. It’s still the Old Union. It’s a strange name.

Samuel Braden’s leadership was severely tested during the three years he was president. He was under pressure from student activists who regularly disrupted campus in a push for change, and from state and local political leaders who wanted him to clamp down on those students.

Samuel Braden

Illinois State University president (1967-1970); died in 2003

The two weeks before the Christmas vacation constituted the longest nightmare in my experience. (From Braden’s letter to the Board of Regents on December 30, 1969.)

Bob Lenz

Sam was calm and effective. He was very thoughtful, but he didn’t panic. He had a real strong sense of values about higher education being a marketplace of ideas, being a place where you could have a difference of opinion.

Charles Morris

We were getting resistance from the community for the things that Braden did at the time. Some felt he had capitulated to the demands of black students.

Bob Lenz

There were a certain number of people in the community who were not supportive of ISU and really wanted the president to fire faculty who made speeches they didn’t like, or wanted him to kick students off campus if they demonstrated, and Sam just had better judgment. He didn’t let those people push him around.

Ed Pyne ’71

Vidette editor

He might’ve been the reason we didn’t have a lot of trouble here.

Alonzo Pruitt

He had a really good heart. To some extent he had some privileged attitudes that came from the times, but I don’t think he himself had an evil heart.

Bob Lenz

Sam had the courage to hire the first black basketball coach at the Division 1 level in the country, Will Robinson. He was ahead of his time in a lot of ways.

Alonzo Pruitt

That was a blip on the radar. It didn’t address core issues.

News of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia sparked protests and campus unrest across the country. Tensions were further heightened when authorities fatally shot students on May 4 at Kent State University and 11 days later at Jackson State University. Illinois State’s campus remained open but experienced its fair share of vandalism, fights over the flag, and protests during these so-called days of May.

John Kirk

Professor of Theatre emeritus (1966-1997)

The whole month of May was full of this tension. Some of us didn’t get much sleep.

Janice Cox

The reason that Kent State happened was because of the invasion of Cambodia, and campuses just erupted. Students were killed at Kent State and Jackson State. And campuses erupted even more. The loss of life scared people.

George Pruitt

And this time some other students lowered the flag. These weren’t black students. And we had great sympathy, all students did, at what happened at Kent State. But that was a different set of issues. What was going through our minds was black folks got killed and we weren’t allowed to raise the flag to half-mast; white folks got killed and somehow it’s OK. And we weren’t happy with that.

Mike Schermer ’73, M.S.E. ’78

Undergraduate student (1969-1973), Student Affairs staff member (1974-2008)

The University paid for all these speakers to come in and talk about all the issues of Vietnam. Probably, that is one of the significant reasons why we never closed. There were many campuses that just shut down. We took a more educational approach.

George Pruitt

A bunch of us went back to see President Samuel Braden. He even called the governor’s office, and now after Kent State, campuses were on fire all over the country. And the governor’s office said it was a matter of local discretion. Basically it was up to Braden. I suggested that we set a date and let’s have a martyrs day. Put the flag back up, but in about a week, let’s lower the flag to half-mast all day long in honor of martyrs for social justice causes of any kind. And let’s have a university teach-in or celebration and discussion about social change and violence, and let’s make it something positive.

Carrol Cox

Professor of English emeritus (1961-1997), former Students for a Democratic Society faculty advisor, husband of Janice Cox

There were huge numbers of students spending time on the Quad. And classes were semicancelled. None were officially canceled, but a lot of students were obviously not going to class.

Bob Lenz

There was some vandalism. Someone lit a small fire in a wastebasket in the union. It was put out in 2 minutes, but the legend of the fire in the union grew exponentially.

Charles Morris

Braden had put in place a curfew and that was to require students to stay in the campus area. We had that for maybe two or three nights. After the Normal City Council heard about that, they thought it was a good idea, so they put a curfew down on the whole Normal city to keep the students under control and confined. Students objected quite vehemently to that.

Read President Braden’s memo to campus about the curfew on May 13, 1970.

John Kirk

We’d form a group. Two pairs of faculty, we’d walk around the campus, all night long. I walked until 3 in the morning, all to discourage people from coming into campus to cause trouble.

Charles Morris

There was confusion about what the perimeter was of the University. Our understanding, and it was agreed to later on, that the boundary was Fell Street but the enforcement guys felt the boundary was School Street. So when the students walked in that direction, police, university and Normal, met them. And that was the worst time that we had. They were chasing, not necessarily to grab and injure, but that happened. There were nightsticks and hands and fists. Assistant Dean of Students George Taylor was hit by a policeman, by a nightstick, I think. That was the most serious event of that type that we had.

Bob Lenz

There were riots elsewhere. Of all the public universities in Illinois, ISU had the least amount of trouble.

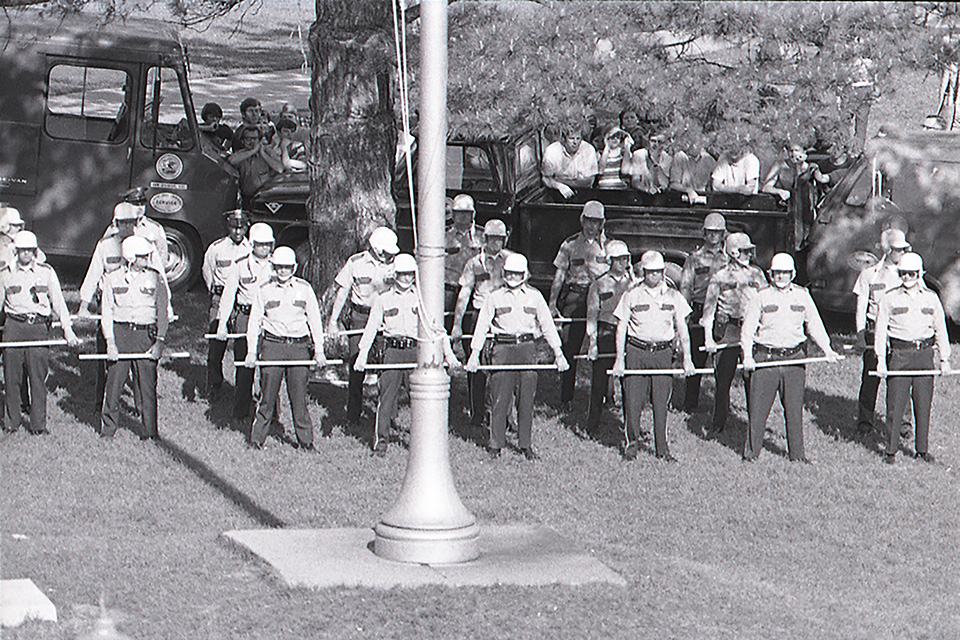

President Braden had agreed to let the flag on the Quad fly at half-mast on May 19, 1970, in honor of Malcolm X’s birthday. That morning a group of construction workers raised the flag and threatened to return if anyone attempted to lower it. Fearing a brawl between the workers and students, Illinois State administrators requested the help of Normal Police. Normal’s mayor refused to protect the campus because he was against the lowering of the flag. Instead university employees ringed the flagpole with ISU trucks, and calls were made to the State Police.

John Freed

The flagpole incident is the culmination of this whole thing.

Bob Lenz

The president had agreed to lower the flag for Malcolm X’s birthday on May 19, 1970, at the request of a lot of students. And a group of hard-hat laborers decided they were going to come to campus and put the flag back up.

George Pruitt

As I was passing the flagpole on the Quad, I saw a bunch of guys who looked liked construction workers. The flag was at half-mast, and there was a security guard standing at the base of the flagpole. They pushed him out of the way and roughed him up a little bit, and one guy shimmied up the flagpole and cut the cord. And they were shouting racial epithets and other things, and they left.

John Kirk

They didn’t think the flag should be at half-mast to honor black militants. The construction workers announced on the radio that they planned to return on their lunch hour and raise the flag for good.

George Pruitt

Then the campus security came. Some maintenance people came and rescued the flag and put it back to half-mast.

Mike Schermer

I’m just watching all of this stuff going on and thinking, “What the hell is going on here?”

Alonzo Pruitt

What I think most annoyed the construction workers that day is that I arranged a protest of people going to the student union to pay for their food with pennies. It interrupted their mealtime. At any rate, I don’t think they were just mad about the flag being at half-mast.

George Pruitt

I got death threats both in my office and at my home. And other students were being treated in a way where they felt threatened. So we got all of the black students together because we felt if there was going to be any violence perpetrated against any of us, we were best off if we were together in one place at one time. Now it’s a different issue. Now it’s not a social justice, free speech issue. Now it’s a security, law enforcement issue.

Dave Anderson

The mayor wanted to call in the National Guard to protect the flag. But cooler heads prevailed.

Charles Morris

The Normal mayor at that time, Charles Baugh, was a typical hardline conservative. And at the time of the flagpole incident, he would not approve the use of Normal policemen to provide protection to the campus. Braden had to make a request to the state.

Dave Anderson

It was a patriotic thing for the mayor.

George Pruitt

State Police came in. We all got together on the other end of the Quad. We decided to play around with softballs because we thought that was a way we could have baseball bats and the police wouldn’t bother us. We basically grouped together because we wanted to protect each other.

John Kirk

There were a bunch of black students down by McCormick gym, stirring themselves up. At the other end of the Quad where the overpass is today, you could see across the street the white hats were gathering, ready to make their move onto campus.

Rose (Osing) Yount

It was getting scarier by the second. At that point, some students—to this day I still cry when I think about it—we joined arms and we stood there across the street from the hard hats to not allow the men to come into campus. And they didn’t. They didn’t cross the street.

John Kirk

Right about that time, we heard the sound of a big engine revving. It was this big ISU truck. It came lumbering onto the Quad, circled the flagpole. Behind it came another truck. And another.

George Pruitt

Someone from law enforcement told the administration that they had to put a definable space around the flagpole—since the campus was an open property—to enforce a no-trespassing issue. So there were cars and trucks that created like a circle-the-wagons around the flagpole.

Bob Lenz

And it worked! It was remarkable. It worked.

John Kirk

The history of ISU and the Town of Normal might be very different without that idea. Tragically different.

Bill Cummings

Neither side really wanted to challenge the larger numbers of state police troopers who were there.

John Freed

It could’ve easily been trouble if those hard hats came back. Think of the confrontation that would have occurred but didn’t. In the end, everybody pulled back.

Bob Lenz

It stopped almost as suddenly as it started, this whole period of turmoil.

Bill Cummings

Things just kind of calmed down. It sort of peaked around the time of that flagpole incident. I think everybody felt spent.

John Freed

The whole country began to settle down.

John Kirk

Thank God it was May. The students left.

George Pruitt

The only downside of that whole thing was President Braden’s decision that he didn’t want to be president. When he came there to be president, it was not to deal with takeovers, and violence, and threatened violence, and marches where people were throwing bottles and rocks at people. He found it distasteful.

Samuel Braden

I simply find that I no longer enjoy grappling with the problems which confront a college president today. (From Braden’s resignation statement on June 11, 1970.)

John Kirk

I felt so sorry for the man. I once saw him speak to a big meeting of students in the old amphitheater. He came offstage in my direction, and I reached out to tell him nice work, and he fell into my arms. He was just shaking all over. I realized what immense pressure this man was facing. He signed on to be a college president, not to handle riots in the street.

Read President Braden’s speech to students at the amphitheater on March 4, 1970.

George Pruitt

We were the only public university where there was no violence. That was a testimony to two things. One it was the leadership of President Braden. And there was also a black student community that really wanted to bring substantive change. But you put those two things together and you have a university that was transformed from the inside because both the leadership of the University and the affected students who were driving it were both committed to making things happen so that the institution would change and be better.

Alonzo Pruitt

You did feel heard. You did feel protected. I never felt like they saw us as the enemy. I respect that so much. It all helped me evolve into the type of person I became.

Virginia Owen

We came through that period not broken in pieces as many campuses were.

While town-gown relations today are better than ever, Illinois State’s campus climate for students of color remains inconsistent, with each student’s experience his or her own. Recent freshman classes have been the most diverse in history, with special programming such as graduation recognition ceremonies becoming annual traditions. Still, racially insensitive episodes spark new conversations. The University’s own 2016 Campus Climate Survey uncovered much room for improvement.

Karyn Aguirre ’86

Black Colleagues Association president

What I think is the biggest difference today is the University is being proactive in opening the conversation. In the 1970s and the 1980s, that was not necessarily the case.

George Pruitt

I can’t tell you how proud I was when President Al Bowman was selected president in 2004. It was a long time, but the continuum that resulted in his presidency, we started in 1967.

Al Bowman

Illinois State University president (2004-2013)

In my mind, what’s really significant in terms of being the first African-American president was the lack of attention it got on campus. I think that’s a positive. My sense was that most people didn’t care.

Rick Lewis M.S. ’87

Retired associate dean of students (1987-2016)

There’s probably not a year that goes by that something doesn’t happen on campus that motivates students of color to respond or react. But the ironic thing about institutions of higher education is our short institutional memory. It doesn’t take long for our students to move forward, or forget, but the students tend to come back the following semester or year, and things have died down. And you just wait for the next flare-up.

Al Bowman

I went to a segregated grade school from first grade until sixth grade. Then, we were bused to an integrated school five miles away. There were lots of racial incidents. People would throw rocks at the bus. So from 1965 to today, the world is a completely different place. I think if you come back 20 years from now, it will be a lot better. It just takes time.

Editor’s note: Some background information for this story came from the Dr. Jo Ann Rayfield Archives; A Place of Education by Roger J. Champagne; and Educating Illinois: Illinois State University, 1857–2007, by John B. Freed.

As one of the first African American Academic Senators, I would love to see our stories told as part of the modernity and evolution of ISU as well.

E. Fizer III ’79

Political Science

I remember hat time in 1970 very well. As a black student I felt various forms of discrimination from the community. The student body and faculty were much better. My biggest disappointment was having a former student from a Chicago school complaining of blatant discrimination from members of the cheer leaders of which she was a member with the sponsor doing very little to negate the behavior. As a result I have had very little to do with the university since my graduation in 1972.

As the most junior of faculty members in Speech-Communication I remember crossing the campus a few times a day to meet with the students in Speech 110 classes. We held class but about 1/3 of the students choose to join or observe the protests. As John Kirk noted faculty were on a sort of informal patrol to keep the peace. What impressed me most were the Vietnam Vets Against the War who also circulated to keep things calm and at time were a buffer between groups. I lived in Normal and was sorry that some of the Normal politicians and police seemed to work to exacerbate and exploit what was a tense situation. The good people of ISU – students, teachers, and colleagues – are always close to my heart.

When I was an undergrad in the late 90s I worked for the construction council locally. I was talking to my boss (an old union guy) about how awesome the new lab building was and he mentioned how Julian Hall (attached to SLB) was named “because they had to name a building after a “black”, only he didn’t say black. It shocked me at the time because I had never heard my boss say one racist thing ever. It strikes me now that he was very likely one of those construction workers at the flagpole or knew some of them. I had no idea that these events even occurred (my parents were at WIU in the late 60s/early 70s). To current students it seems completely obvious that the Science Lab Building is attached to a building named for a brilliant chemist. The fact that it may have been named for Julian because he was an activist instead because he was a scientist does not change his importance as both.

Kristen Eilts BS ’98, MS ’17

Chemistry