At first glance, the two plays in the Illinois Shakespeare Festival’s 2021 season could not be further apart. Measure for Measure explores the seedy underbelly of a crowded city inspired by the London of Shakespeare’s day, while The Winter’s Tale evokes the expansive landscapes of fairy tales, classical poetry, and the English countryside. Measure for Measure takes an unflattering look at human nature, prone to sexual impulses and hypocrisy, whereas The Winter’s Tale believes in our capacity to do good and change for the better.

However, there are some interesting connections to make. First, both plays defy genre. They are classified as comedies in the First Folio, but Shakespeare takes the traditional happy ending of comedy in new directions. On one hand, both plays give audiences the resolution they expect: reconciliations, marriage proposals, and reunited families. Yet the happy conclusions are stifled by lingering feelings of injustice, trauma, and grief. Coinciding with the turn towards tragedy in his mature career, Shakespeare seems dissatisfied with comedic formulas, wanting to write endings that cut close to the bone.

Although this is by no means exclusive to these two plays, Measure for Measure and The Winter’s Tale also feature female characters who suffer sexual abuse or accusations of infidelity, calling attention to the precarious status of women in Shakespeare’s time. Interestingly, a female character remains silent at a crucial moment in each play’s last scene. Isabella in Measure for Measure does not answer Duke Vincentio’s unprompted marriage proposal, leaving it unclear whether they will be wed after the curtain goes down. Queer Hermione in The Winter’s Tale does not say anything to her guilt-ridden husband after she miraculously comes back to life. These pointed silences have been interpreted in different ways, changing the tone of the plays’ endings. Are these women submitting to their situation? Are they being silenced? Or is their silence a form of resistance, refusing to assure their male counterparts and the audience that all is well?

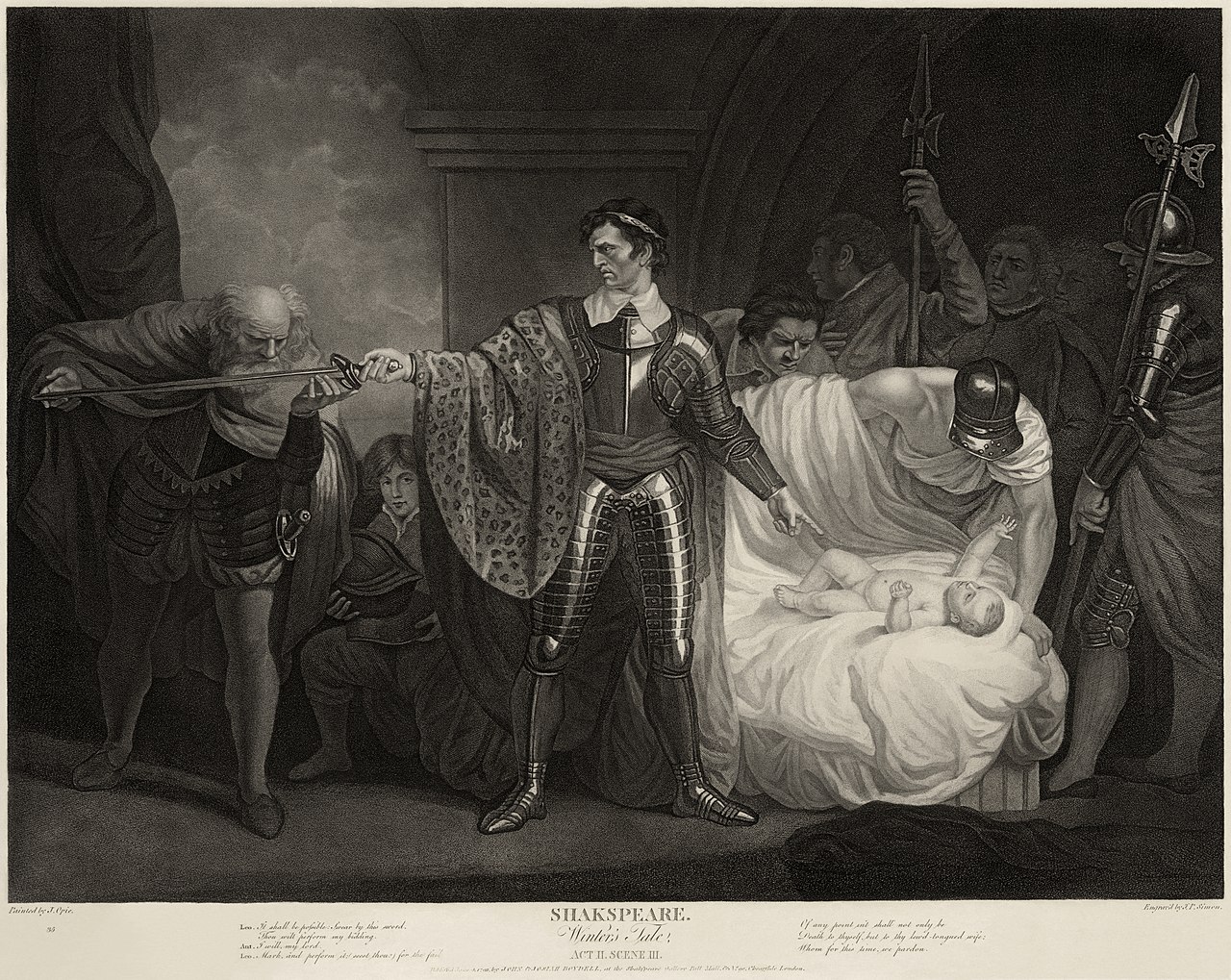

This leads to yet another parallel between the two plays: The conclusion rests on whether these wronged women forgive their abusers. Isabella is faced with a tough choice: does she act to stop Angelo’s execution? This is the man who abused his office to get her to sleep with him and refused to grant clemency to her imprisoned brother. Meanwhile, Hermione transforms from a statue into living flesh to hear out Leontes’ confession of shame and remorse. But no magic in the world can undo the pain he inflicted on her, nor the death of their son Mamillius. Be benevolent. Let bygones be bygones, the world tells these women. But can they forgive?

This question can have profound implications, as forgiveness relates to Christian ideas of penitence and repentance, as well as religious practices such as confession and penance. Whether Angelo and Leontes can be forgiven raises a more fundamental question that Shakespeare’s Christian audiences would have been invested in: Can the sinner be saved? It seems more than a coincidence that these plays are rife with religious symbolism: For example, the pun on angels (and devils) in Angelo’s name, echoes of the Sermon on the Mount in the title “Measure for Measure,” the painted statue of Hermione as an allusion to the Virgin Mary, and the connection to Paul the Apostle in the name of Paulina, who presides over Hermione’s resurrection.

Yet the question of forgiveness is not only a religious one. In her book Shakespeare and the Grammar of Forgiveness (2013), Sarah Beckwith envisions Shakespeare as a moral philosopher, using drama to probe the limits of mercy in social life. She argues that Shakespeare used the theatre to demonstrate the power of forgiveness to bring people together and imagine a way forward. Here, Beckwith is drawing from the work of the 20th-century philosopher Hannah Arendt, one of the most influential modern thinkers on this subject. Arendt pointed out that forgiveness is by nature social; you cannot forgive yourself for your wrongdoings and move on. As such, it is predicated on mutual understanding, consent, and empathy. This is what distinguishes forgiveness from a pardon or absolution. Beckwith writes: “The authority of the forgiver and the forgiven must be found and granted by each to each.”

In Measure for Measure, Shakespeare uproots these foundations for forgiveness. In trying to fix his city’s problems, Duke Vincentio turns into a cunning puppeteer, keeping everyone in the dark until he can stage his grand scene of mercy on Vienna’s streets. With the public gaze bearing down on them, can Isabella and Angelo—forgiver and forgiven—really see each other? Notably, Isabella does not say anything to Angelo after asking (or being compelled to ask) the Duke to spare his life. In fact, Shakespeare gives her no more lines for the rest of the play, including when Duke Vincentio proposes to her. The multi-nuptial happy ending can ring hollow depending on how directors and actors interpret Isabella’s silence. Things wrap up too neatly—all according to the Duke’s master plan.

Shakespeare reminds us that forgiveness never comes easy; maybe it did not come at all in this play. In recent years, the #MeToo movement has brought attention to numerous cases of sexual misconduct and violence: brave Isabellas up against daunting Angelos. Measure for Measure offers an opportunity to think about the ways in which ideas of repentance and forgiveness can be misused in these situations. What does it mean for an accused perpetrator to make a public show of expressing regret without speaking directly to their accuser? How can we tell the difference between a genuine apology and a forced one? And is one entitled to forgiveness just because they said they are sorry? Does society pressure people (especially women) to forgive for the sake of “moving on,” whether or not they are willing?

These are thorny questions, which might lead one to favor the “hard” ideals of justice and answerability over “soft” virtues like mercy and compassion. But Arendt and Beckwith believe that forgiveness plays a vital role in human life. Arendt asks us to imagine a world where forgiveness is impossible. Our mistakes would be irrevocable, our flaws fatal. Therefore, to forgive means to offer hope—not a naïve hope that things will somehow work out in the end, but a solemn hope that we can work to make the future better than the past. Beckwith insightfully notes that this difference between despair and hope is also the difference between Shakespearean tragedy and his post-tragic theatre of forgiveness, including The Winter’s Tale. In his last plays, Shakespeare was concerned with the possibility of life after tragedy. If this were “The Tragedy of Leontes,” the play would have ended with news that his wife and son had died, and his newborn daughter is lost forever. But Shakespeare writes two more acts after that, setting the stage for his redemption. The statue coming to life may seem like a whimsical conceit, but the emotions are painfully real. Perhaps Shakespeare relied on magic, miracles, and fantasy in his late work because he recognized how difficult it is to be truly redeemed in real life. And so, the happy ending of The Winter’s Tale resonates on two registers. Hermione comes back to life, but other victims of Leontes’ wrath remain dead. The royal family is reunited, but only after losing sixteen years of their lives. And while Hermione does speak in the final scene, she only gives her blessings to her daughter Perdita. She has no words for Leontes—at least not yet.

As human beings, we want to believe that we can leave the past behind and look to a better future. That belief is what brought many of us through the tribulations of 2020. But when you see Measure for Measure and The Winter’s Tale live at the Ewing Theatre this summer, I invite you to also think about the difficult work that needs to be done to move forward. These plays suggest that repentance and forgiveness are some of the hardest things that we can accomplish. But if we manage to do this with honesty and mutual understanding, Shakespeare seems to believe that tragedies can eventually be overcome.

Beyond the Stage is an article series on the dramaturgy of Shakespeare productions in the current season. These articles explore the plays from a wide range of perspectives, from history and literary criticism on the original works to interviews with directors and creative teams.