When you work in the world of nanotechnology, microorganisms, and tiny geological objects, a microscope can be your best friend in the research lab. Dr. Mahua Biswas, assistant professor of physics at Illinois State University, has spent a couple of decades pursuing the kind of work that requires a specialized microscope. Until now, she’s had to travel to do her work.

A recent grant of $403,900 from the National Science Foundation (NSF) has brought a state-of-the-art electron microscope to campus, now settled into its new home in Felmley Hall of Science Annex 147. Thanks to Biswas, acting as principal investigator (PI), and the co-PIs of the grant—Drs. Uttam Manna, JunHyun Kim, Tenley Banik, and Jan-Ulrik Dahl—researchers of all levels will soon be able to use this new instrument to pursue their scientific passions.

Biswas, who is also a visiting research scientist at the world-renowned Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, touched on a few important things to know about Illinois State’s new electron microscope:

Exactly what is this microscope?

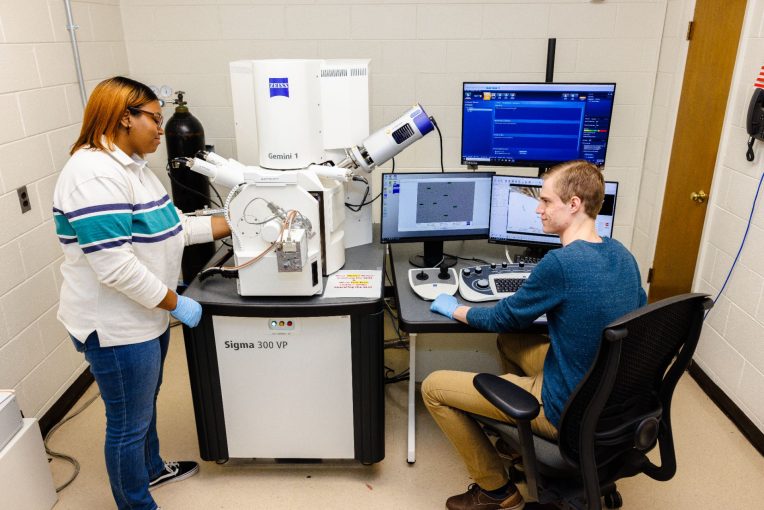

It’s called a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and more specifically this one is a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM). The SEM is an instrument that can produce a largely magnified image by using electrons (a subatomic particle) instead of light to form an image and can provide elemental information from the sample of interest. A beam of electrons is produced at the top of the microscope by an electron gun (field emission electron gun for an FESEM) held at ultra-high vacuum. The electron beam follows a vertical path through electromagnets and lenses, which focus the beam down toward the sample, all of which are held within a vacuum. Once the beam hits the sample, electrons and X-rays are ejected from the sample that can be detected by specialized detectors and processed by software for producing images and elemental information. The newly acquired microscope is a Zeiss Sigma 300 VP. Carl Zeiss is the name of the vendor, and Sigma 300 VP is the particular model.

How does it differ from a microscope that everyone has used in school and at home?

The traditional light microscope, which has been around for centuries, cannot see beyond ~1,000 times the magnification (equivalent to resolution of ~1 µm object) while, Biswas said, the best scanning electron microscope gets you 1 million times the magnification (equivalent to resolution of ~0.5 nm object). Illinois State’s FESEM can be utilized to see objects as small as 1nm. Apart from the imaging capabilities at different modes with different detectors it has an X-ray detector known as an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) for detecting emitted X-rays that can be utilized to identify elements (such as silicon, aluminum, titanium and carbon) present in the sample. It comes with a software option that delivers expert results for beginners and saves time on training. Illinois State’s FESEM has a range of capabilities.

“Physicists and chemists like some of us are doing research with materials in the nanometer scale, geologists are looking into rocks, minerals and microplastics, and biologists are looking into bacteria and viruses,” Biswas said.

Who can use it?

Internal users of Illinois State should contact their respective FESEM facility co-directors, and all other users for research and education purposes, should contact Biswas, the facility’s director, to get started. One of the missions with the microscope involves educational outreach, which includes making it available to K-12 institutions, community colleges, and universities. Eventually, Biswas plans to reach out to local companies and industries to see if they have an interest in using the microscope. Even University Galleries is interested in helping showcase it to the community. Contact information about.illinoisstate.edu/fesem/contact is available for all prospective users.

What’s involved in purchasing an FESEM?

Such a purchase requires money, of course, but also time and people.

“The grant, known as the NSF-Major Research Instrumentation (MRI) grant, is for purchasing expensive instruments for campus-wide and regional use that would otherwise not be possible to purchase using institutional or personal research grants,” Biswas said.

There was a lengthy, complex grant application process through the (NSF) that had to be managed, submitted, modified, and re-submitted. Biswas was joined by a team of collaborators that totaled 25 in all. The group included several co-PIs and a group of individuals classified in grant terminology as “major users” of the microscope. Biswas described it as a “very extensive, and rigorous process of identifying the instrument that will serve the purpose of interdisciplinary research, of planning the long-term maintenance of the instrument, and of justifying it to NSF in the proposal, that required meeting with multiple vendors, faculty users, and ISU administrators.”

What was the timeline like?

Biswas came to Illinois State in the fall of 2020 and began the grant proposal process almost immediately. She arrived in the middle of the pandemic and got busy drafting the preliminary proposal to Research and Sponsored Programs (RSP) at Illinois State for institutional approval. The application was submitted to NSF through RSP in January 2021, with word coming back in June to modify the budget of the proposal. Official approval—for $403,900—was received in August 2021, with the grant technically starting in September. The purchase order was placed in December 2021, and the microscope was delivered at the end of October 2022. Once Biswas and her co-PIs complete their advanced training, the FESEM should be available for wider use in the summer or fall. All the research users will be required to have a certain number of hours of training before they will be allowed to self-use the instrument.

What are your biggest hopes for this microscope?

For it to expand interdisciplinary research across campus and in Central Illinois—which Biswas said was another important component of the NSF proposal.

“What we really want is to see it utilized to its fullest capacities within the scientific communities, to perform cutting-edge research, to publish scientific papers, to encourage school kids in STEM” Biswas said. “We really want to use the instrument for science and outreach for many years to come by maintaining it well.”