Rose Marshack, director and professor of Creative Technologies at Illinois State University, is a founding member and bassist for Poster Children, an indie rock band formed in 1987. Over the past 35 years, Poster Children has played more than 800 shows in the U.S. and Europe while releasing 10 albums.

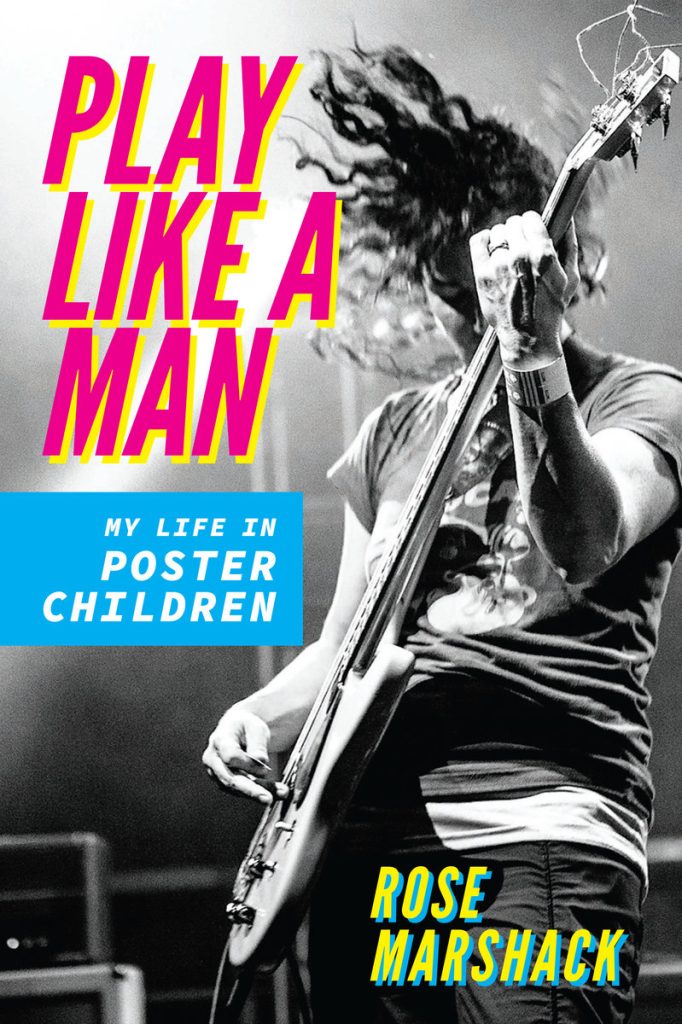

Marshack chronicles her experience “rocking while female” in a new book, Play Like a Man: My Life in Poster Children. Shortly after it was released in February 2023, Marshack took a moment to discuss her book, reflect on her career, and give advice to aspiring rockers.

Why did you decide to chronicle your experience as bassist for Poster Children in a book?

Poster Children had been touring around since around 1991, and what that meant for me was lots of time in a van reading, and then stopping in cities all over the U.S. and meeting interesting people and learning all about their lives. This was before cellphones and social media. Sleeping on people’s floors especially helped us get to know people and how they lived.

So, I wanted to document all these incidents, and when Prairienet, the freenet in Champaign-Urbana became available to its citizens, I took advantage of that and learned html and started posting my tour reports up on the web. This was 1995, so you might call that one of the first blogs.

People seemed to enjoy my writing, and every so often someone would suggest I compile it into a book. Through some wonderful contacts I sent a proposal to UI Press, and Laurie (Matheson) and the others at the Press were just so incredibly supportive.

I have had so much help for this project, my colleagues—especially (Professor of Ethnomusicology) Dr. Ama Oforiwaa Aduonum and (Associate Professor of Art History and Visual Culture) Dr. Melissa Johnson at ISU—constantly asked me how my writing was going. My partner, (Professor of Creative Technologies) Rick Valentin, helped me along, and I really appreciated all the peer review stages that happened through this process.

During the indie rock breakthrough of the 1980s-2000s, you say in your book that women seized an elevated profile in music. To what do you attribute increased opportunities for female musicians during the indie revolution?

Indie rock had a much more DIY attitude than commercial rock. You might even say the stakes were lower. These were grassroots communities who had less gatekeepers—like commercial radio, major labels, etc. So, in that respect, I think it was easier for more women to join bands; and, in fact, there were probably a lot more bands to join. In the book, though, I wrote about some of the more negative impacts of an “elevated profile,” for instance, the larger commercial magazines declaring it “The Year of The Woman” and spending an issue of a monthly magazine on only bands with girls in them; then going back to “normal” all the rest of the time. The tokenism, I wrote, implies that it’s an oddity that a female could be a musician in a band.

From your firsthand perspective, how did new technology transform the recording and marketing of music in the 1990s? Were punk bands, such as Poster Children, uniquely equipped to embrace advances in digital technology?

By the time we were making our first few independent albums, we were able to record in home recording studios—for example, Steve Albini’s very professional, all analog home studio was accessible to us and affordable, because he wanted to help out the punk and indie community. Our tiny computers allowed us to create our own cover art.

Then, on the major label, the internet allowed us to self-publish our ideas, our tour reports, and create online communities where people who were our fans could learn from each other. So, during our years and albums on major labels we had access to more money and distribution, but by the time we left the majors and went independent again, the whole world had changed. Our preparations on the internet made the major label unnecessary. We didn’t need their help to get our word out, to record our music, or to distribute our music. The internet allowed flat access to everything.

Were punk bands like us uniquely equipped? It’s possible, because with punk rock, you’re looking to communicate and connect with others, whether it’s through self-published zines or driving your own van and booking your own shows. You’re looking to create a community and learn from each other, and digital tools were great at granting access to these types of outcomes. Learning how to use technology in college didn’t hurt either, since that gave us experience thinking about digital media as tools.

You’ve worked as a computer programmer and teacher throughout your 35 years/more than 800 live shows across the U.S. and Europe with Poster Children. How have you managed to balance it all?

Through collaboration and teamwork. My other half, Rick Valentin, does all this same stuff with me! We were both computer programmers at the same job in the beginning, and now, we are both teachers in the same unit. We played all these shows together, and traveled around, bounced ideas off each other, created together, went back to school together. So, I had help. It’s really like two people were building this world, not just one.

I’ve learned over the years that the more you collaborate with others, the more you get out of it. So, learning from people in other bands, learning from students, community-building—all of this helps a lot.

What’s your advice for aspiring rock stars?

What exactly are you looking for, in being a “rock star?” Are you looking to reach a lot of people? Would you compromise your music so you could become more famous? Are you wanting money?—Then don’t become a rock star! You must decide what you want your outcomes to be. Make sure you make music, or art, or anything else creative, because you are called to do it—because you cannot NOT do it.

Also, a career in the arts is not always fun, or fulfilling, or comfortable. You may spend a lot of time second-guessing yourself, your art, or even wondering why you are not more famous. So, for me, the reason this all has worked out so well is that I’m in a constant state of bewilderment that I actually get to create art, or music, and connect with others who enjoy listening to it. I don’t really have any other goals.